Jacky Godoffe might be one of the top route setters in the world, but he got off to a rough start. It was 1993, and the French climbing federation threw him right into the deep end. They asked him to set the women’s finals route for the French National Championship, the only hitch being, he had never set before.

A bit overzealous, perhaps, he set hard moves off the ground. Out of the 12 climbers in finals, 10 or so fell before the first bolt. “It was a disaster, a nightmare,” he says. “But, you know, I didn’t know anything about setting, and I realized I had missed something.”

Undeterred, Godoffe kept at it and learned from his mistakes to become one of the most respected route setters in the field. He created the universal speed climbing competition route—which we still use today, nearly 15 years after its inception—served on the IFSC Route Setting Commission for 10 years, and literally wrote the book on route setting. The 61-year-old climber still coaches and sets for the French climbing federation, and is one of 30 IFSC-certified World Cup route setters, who set the World Cups every year.

“I was a very poor setter at first, even though I was a strong climber,” he says. “But, I realized I had something to learn, and I’m still learning today.”

We spoke with Godoffe to hear about his creative process, the evolution of route setting, and the lessons he’s learned from nearly three decades in the profession.

Q&A with Jacky Godoffe —

When did you start climbing, and how did you get into route setting?

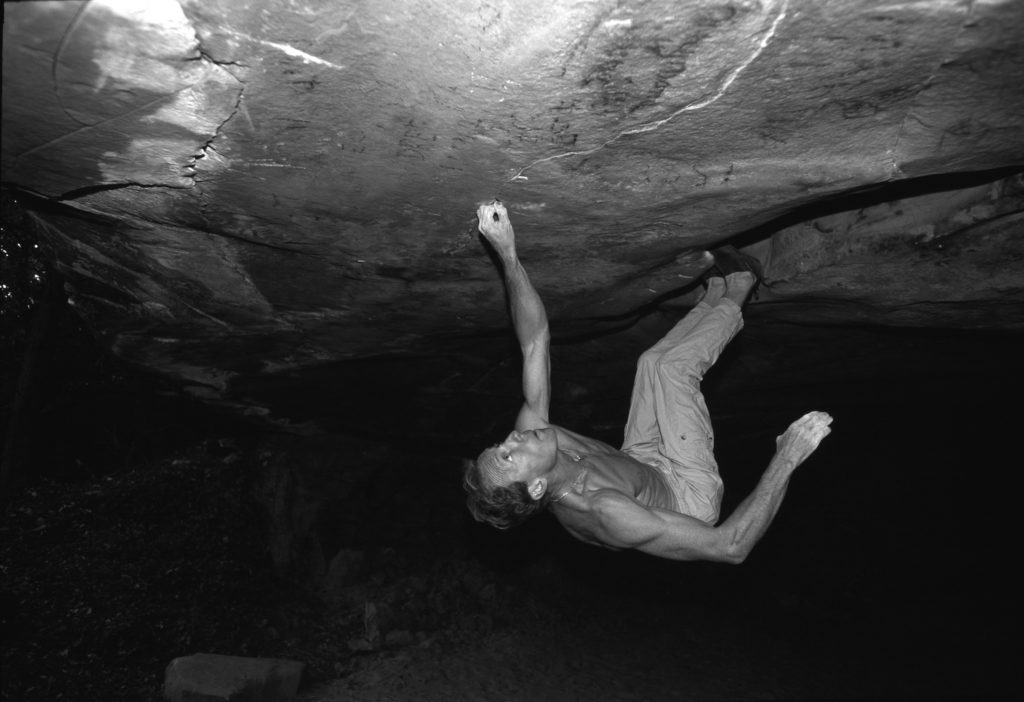

Even though I lived in Fontainebleau, I start climbing really late—when I was 20 years old—but it was an immediate addiction. I climbed a lot in the forest, then entered the early days of competition climbing. In the next moment, I was teaching, and I passed a new accreditation to join the French climbing federation as the first trainer.

That’s when I realized route setting was quite interesting. It felt like an extension of what I was doing in Fontainebleau, discovering and establishing new boulders. It’s a similar process to find new tricks, to prepare the playground for others, and to share it with others. So, I started with route setting probably 10 years after my addiction to climbing began.

After your nightmare setting experience at the French National Championship, how did you improve?

I set in a lot of competitions, and step by step I became better. I made a lot of mistakes at first, and these were always on my mind. Not mistakes, per se, but ideas I thought were good, which didn’t work in the end. To be a good route setter, you need to learn from your failures, and the more you learn, the more you realize how much you still have to learn. It’s a never-ending story, honestly.

Setting takes experience, and through it I’ve had the opportunity to set all around the world with different people, in different places. So, I got better from exchanges with other setters. It’s exactly the same with climbing—if you want to get better, the fastest way, for sure, is to climb with other strong climbers. You will learn and you will observe and you can integrate that knowledge. It’s the same for route setting. It’s the same for everything [in life], I would say.

“To be a good route setter, you need to learn from your failures, and the more you learn, the more you realize how much you still have to learn. It’s a never-ending story, honestly.”

What are some other important skills when it comes to route setting?

Curiosity, I would say, and the ability to manage your ego. That’s not so say you should abandon your ego—it’s important to have one when you are setting, because you need determination to achieve your goals. But at the same time, setting requires teamwork, so it’s very important to listen to the people around you. It’s a fine balance.

In the early beginning, I didn’t listen to others. But I learned that the final result is the result of the team. It’s the result of a process. You have a special target in a competition—it’s not all about you. You don’t have to please yourself, you have to please the people that come for the climbing, and to also please the people that come to watch.

Can you describe your setting process? How do you go from a blank wall and a pile of holds to a finished boulder?

First, you have to fix the target for the climb. Is it for men or women in a world cup, for a gym, for youth? Then you need to decide on the goal or style of your boulder. For example, will it be powerful and dynamic or technical and require patience? Once you know your target and your goal, you can start choosing the holds.

From here, there are a lot of different approaches to route setting. You could try to replicate something you climbed in your past, or you can let the holds inspire the track, knowing that in the end you need to hit the target.

When you have finished your draft, which can take around 40 minutes or so, then you have a short try alone to check if it’s more or less okay for the difficulty, the goal, the target. If you think it’s okay, then you can ask the setting team to try it and give critique to make it better. The duration of this teamwork depends on the quality of your draft. Sometimes it’s very fast, sometimes we struggle for hours adjusting the same boulder or route, and sometimes it turns out that the original idea has to be abandoned and you need to start all over. It’s a process.

How do you set a competition to be fair for all heights?

In most classical sports, the athletes are the same size, more or less. But in climbing you can have super small or super tall climbers who are all very strong and talented. Not all climbs can be set for all sizes—this is impossible. But on average, you need to have a diversity of setting. For some boulders, small climbers will have an advantage, and the tall ones will be embarrassed. The opposite is true, as well. Overall, in modern setting, I would say it’s not a great advantage to be either super tall or super small.

It’s important to have different size route setters so you can make the setting fair and more interesting for everyone. The same goes for the gym. If all of the setters are taller than average and don’t pay attention to the smaller customers, they won’t be happy.

How does competition setting differ from everyday gym setting?

When you set for competitions, you set for ranking. You need to have something selective—not too hard, and not too easy—to spread out the climbers. This is the easy part, I would say, if you know the climbers. I’ve set for over 25 years, so I know more or less the abilities of each strong climber.

For me, the main thing is to also set for the audience. If we want our sport to grow, it needs to captivate people, even those who are not climbers. So we need to pay attention to the aesthetics of the moves, to make something dramatic, to tell a story. Sometimes we succeed, sometimes we fail, because it’s not easy to do. There’s a lot of different elements to mix.

In your mind, what makes a good route or boulder?

Over the years, I learned to not judge a climb based on the competitors. That’s not a good answer in the moment, because when they succeed they are happy and when they fail they’re unhappy. For me, the best feedback, first of all, is the ranking. If it’s good, we are happy. But then I look at the faces of the people in the audience. If their eyes are wide open and people are smiling, I know that it was good.

This goes for climbing gyms, as well. If you set for customers, you also have to pay attention to what they want, surprise them, and encourage them to try new things. When the customers climb the boulders you have set, you have the results and the feedback right there, and then you can realize what you have to do to make it better the next time.

In general, I would say, that as route setters, we ask questions and climbers give answers. That’s it. And the result of a good competition is when this question and answer meet together.

“In general, I would say, that as route setters, we ask questions and climbers give answers. That’s it. And the result of a good competition is when this question and answer meet together.”

You created the universal speed climbing competition route—can you tell us more about it?

The idea of the speed route was to make something absolutely different from the rest of climbing. The unique holds are designed to be grabbed in three different ways, and they are supposed to be a caricature of a bird flying. [laughs] I don’t know if it’s that obvious, but, yes. I set the route in a couple of days, and in total with the hold design, I would say, it was done in three months. I think for how fast it was, it was cool.

Do you think they should change the speed competition route every now and then?

Oh, yes. It was not my idea at the time to create a route that lasted for 15 years or longer. When I was on the IFSC commission I asked them, maybe three or four times, to change it after five years or so. But now that every gym or team in the world has bought all these holds, I think they were probably afraid if they change everything it could be a mess. In my opinion, it should be changed to be more connected to our world now, because it exists in the world of 15 years ago.

How has setting changed over the years?

At the same time, it has changed a lot and not at all, I would say. You still have a blank wall, some holds, your target—the people who will climb—and you have to find something adapted to them. That is all the same.

What has changed is the evolution of the materials—the holds, the volumes, and the walls—which is amazing. With these new types of holds, we’ve seen the introduction of new styles. You can play differently and you can try new things. Even now, we are still able to imagine new things for the future.

I’ve also seen the evolution of the best climbers and training. Climbers now train super hard and become super strong very young. So, we’ve had to not only raise the difficulty of setting, but also introduce new factors like greater complexity and a time limit for climbing, which means they have less of a chance to top. Setting now is a mix of these three elements: the intensity, the complexity, and the risk. As a setter, you mix these different elements like a DJ, pushing one harder, controlling another, to find the perfect balance. You don’t want the boulder to be so easy the climbers can flash it, but you also don’t want it to be so difficult that nobody can do it.

Lastly, there’s been a huge progression for women. I remember when we were setting for girls 15 or 20 years ago, we set with normal shoes because if we set with climbing shoes—I’m not joking—it was too hard. And now, even with climbing shoes, come on, it’s super hard. The evolution of woman in competition climbing has been amazing.

Having set for nearly three decades, do you still find it interesting?

Oh, yes. [laughs]

Obviously, I’m way less strong than I was before. But what is interesting, I would say, is that my setting was worse when I was in top shape because in general I set too hard. I set more for myself. Even when you are a strong climber, you don’t necessarily have all the skills possible. You might be able to muscle your way up a climb, but still lack good balance and coordination, for example. I think I became better at setting with time because I learned how to be conscious of others with different skills.

So, for me, I think it is still super, super motivating to set. I set three or four times per week in the gym for the French team, and I’m still super psyched, yes. It’s always a new story. I love it because I can share emotion with people all over the world, between climbers, judges, other route setters, and spectators.

What has setting taught you over the years?

Route setting is not about perfection, but a research of emotion. We always have to remember why we are setting. I don’t set just to put holds on the wall. I set to tell a story. I set to propose emotion. And every day I set, I never forget why I’m doing it and why I’m so happy. That’s how I’ve been in the game for so long.

Never forget why you’re doing what you’re doing—and that goes for life in general, I would say. Whether you’re an athlete or a musician, if you understand why you are doing these things, I think you’re not only going to be better at them, but also happier.

I don’t know if that’s the best way to live, but it’s my way to live. And after all these years, I’m still super happy.